Confused by fluid terms like viscosity and drag? This confusion can hinder product design. I'll clarify these distinct but related concepts for you.

Viscosity is a fluid's internal resistance to flow (thickness). Drag is the external resistive force an object experiences moving through a fluid. Viscosity contributes to drag.

Understanding fluid dynamics is key for many industries. My customers, like Jacky, a lab instrument distributor in Italy, often ask about fundamental concepts. He knows his clients—who might be formulating anything from cosmetics to industrial lubricants—need clear explanations. If you've ever wondered how viscosity truly differs from drag, you're about to find out. At Martests, we believe that a solid grasp of these principles helps our partners better utilize our viscometers and serve their markets. Let's dive deeper into these terms, starting with viscosity itself, a property our Martests viscometers measure precisely.

What Exactly is Viscosity, and How Does It Affect Fluids?

Does "thick" or "thin" fully capture viscosity? Misunderstanding its nature can lead to poor material selection or process inefficiencies in many applications.

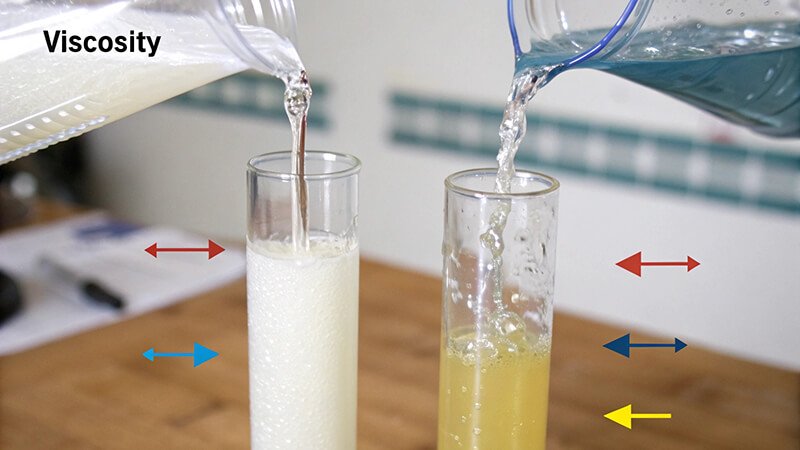

Viscosity is a measure of a fluid's internal friction or resistance to flow. High viscosity means it flows slowly (like honey); low viscosity means it flows easily (like water).

Viscosity is a fundamental property of fluids – this includes both liquids and gases. You can think of it as the "stickiness" or "internal friction" of a fluid. When I'm discussing our rotational viscometers (like our rotating spindle viscometer models, or even more specialized cone and plate viscometers) with clients who are purchasing managers for large instrument distributors, I often use simple analogies. Imagine pouring honey from a jar, and then imagine pouring water. Honey has a high viscosity; its molecules resist moving past each other quite strongly. It flows slowly. Water, on the other hand, has a low viscosity; its molecules slide past each other much more easily, so it flows quickly.

This internal resistance arises from the cohesive forces between molecules within the fluid.

- In liquids: Viscosity is primarily due to the intermolecular attractive forces. Stronger forces between molecules generally mean higher viscosity. As temperature increases, these forces weaken, so the viscosity of most liquids decreases.

- In gases: Viscosity is mainly due to molecules colliding and transferring momentum as they move around randomly. Unlike liquids, the viscosity of gases usually increases with temperature because molecules move faster and collide more often.

At Martests, our range of viscometers, including cup and bob viscometers, are designed to measure this property accurately under controlled conditions. This precise measurement is vital for industries ranging from food processing (think ketchup consistency) to pharmaceuticals (ointment formulation) and petrochemicals (lubricant quality). Getting viscosity right affects product quality, performance, and even processing costs.

So, What is Drag Force in the Context of Fluids?

Ever felt your hand pushed back in the wind when moving? That's drag, but ignoring its complex nature can lead to inefficient designs, wasting energy and resources.

Drag is a resistive force that opposes the motion of an object through a fluid (liquid or gas). It depends on the fluid's properties, the object's shape, speed, and size.

Drag is not a property of the fluid itself, but rather an interaction force. It occurs when there's relative motion between an object and a fluid. If you stick your hand out of a moving car window, the force you feel pushing your hand back is drag. If a ship moves through water, it experiences drag. Even air flowing over an airplane wing creates drag (alongside the crucial lift force).

Drag force generally has two main components:

- Skin Friction Drag: This component is directly related to the fluid's viscosity. It's the friction between the fluid layers sliding past the object's surface. Think of it as the fluid "sticking" to the object and resisting its motion. A smoother surface generally means less skin friction drag. The more viscous the fluid, the higher this component of drag will be.

- Pressure Drag (or Form Drag): This depends heavily on the object's shape and the pressure difference it creates between its front and back as it moves through the fluid. A bluff, non-streamlined object (like a flat plate held perpendicular to the flow) creates a lot of turbulence and a large low-pressure area behind it, leading to high pressure drag. A streamlined shape, like a teardrop or an airfoil, minimizes this pressure difference and thus reduces pressure drag.

Several factors influence the total drag force:

- Fluid Density: Denser fluids generally produce more drag.

- Relative Velocity: Drag typically increases with the square of the velocity. Go faster, and drag increases a lot.

- Object's Size and Shape: Larger objects and less aerodynamic shapes experience more drag.

- Surface Roughness: A rougher surface increases skin friction drag.

- Fluid Viscosity: As mentioned, this directly impacts skin friction drag.

Understanding and minimizing drag is crucial for designing efficient vehicles (cars, planes, ships), optimizing flow in pipes, and even improving the performance of athletes in sports like swimming or cycling.

How Do Viscosity and Drag Differ Fundamentally?

Are viscosity and drag interchangeable terms when discussing fluid behavior? Confusing them can lead to flawed analysis in fluid mechanics, impacting product performance and overall efficiency.

Viscosity is an internal property of a fluid itself (its inherent resistance to flow). Drag is an external force exerted on an object due to its motion through a fluid. Viscosity is one factor that contributes to drag.

While both viscosity and drag relate to resistance in fluids, they are fundamentally different concepts. Viscosity is an intrinsic, measurable property of the fluid itself. It describes how easily the fluid deforms or flows internally, due to the interactions between its own molecules. You can take a sample of oil to a lab and measure its viscosity with one of our Martests viscometers even if that oil is just sitting still in a container. This is a critical parameter for my B2B customers who supply quality control labs or R&D departments; they need reliable viscosity data for product formulation and compliance.

Drag, on the other hand, is an external force. It arises specifically from the interaction between a fluid and an object moving through it (or, equivalently, fluid moving past a stationary object). Drag doesn't exist if there's no relative motion between the object and the fluid.

A key point I often emphasize to customers like Jacky, who supplies instruments to companies developing new coatings or lubricants in Italy, is that viscosity contributes to drag. Specifically, viscosity is the primary cause of the skin friction component of drag. A more viscous fluid will generally cause more skin friction drag on an object moving through it. However, the total drag force also depends on many other factors completely independent of viscosity alone, such as the object's shape, its speed, and the fluid's density. For example, two fluids might have the same viscosity, but if one is much denser, it could produce more drag.

Here's a table to summarize the main differences in a structured way:

| Feature | Viscosity | Drag |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | An internal, intrinsic property of a fluid. | An external force experienced by an object interacting with a fluid. |

| Definition | A measure of a fluid's resistance to shear or flow within itself. | A resistive force opposing the relative motion between an object and a fluid. |

| Exists When? | Always present in a fluid, regardless of motion of external objects. | Only exists when there is relative motion between an object and a fluid. |

| Depends On | Fluid type (molecular structure), temperature, and sometimes pressure. | Fluid properties (including viscosity and density), object shape, size, speed, surface roughness, and fluid compressibility. |

| Measurement Unit | Typically measured in Pascal-seconds (Pa·s), poise (P), or centipoise (cP). | Measured in units of force, such as Newtons (N) or pounds-force (lbf). |

| Primary Effect | Determines how easily a fluid flows by itself or through a channel. | Determines how easily an object can move through a fluid, or the force a flowing fluid exerts on an object. |

| Relevance | Critical for lubrication, fluid transport, material processing. | Critical for aerodynamics, hydrodynamics, vehicle efficiency, energy losses in pipes. |

Understanding this distinction is not just academic; it has practical implications. For instance, when formulating a lubricant, high viscosity might be good for film strength but could increase energy losses due to drag in high-speed applications. It's a balancing act, and precise measurements, like those from our Martests viscometers, are essential for informed decisions.

Conclusion

Viscosity is a fluid's internal flow resistance. Drag is an external resistive force on an object moving in a fluid. Viscosity contributes to drag, but they are distinct.